Treatment Patterns and Clinical Outcomes in Elderly Patients with Breast Cancer

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Although the number of elderly patients with breast cancer is increasing as the population ages, their treatment is controversial. We evaluated the prognostic factors associated with survival in elderly breast cancer patients and assessed the impact of comorbidity on prognosis.

Methods

This study included 362 patients (aged ≥65 years) who underwent surgery for breast cancer in our institution between 2003 and 2014. The patients were divided into early-aged (65–74 years) and late-aged (≥75 years) groups. Comorbidity was parametrized using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI). Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to analyze overall survival (OS) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS). Prognostic factors were evaluated by Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

The surgical method, subtypes, stage, and oncological features were similar between early- and late-aged groups; however, smaller proportions of patients in the late-aged group received chemotherapy (12.9% vs. 45.5%) and endocrine therapy (55.3% vs. 73.3%). In multivariable analysis, the poor prognostic factors associated with DMFS and OS were high CCI, high histologic grade, and advanced stage. Chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and radiotherapy were not significantly related to DMFS and OS.

Conclusion

In this study, adjuvant treatments did not affect the prognosis of elderly patients with breast cancer. To clarify the effects of adjuvant therapies in these patients, a large-scale retrospective study that considers not only tumor characteristics but also life expectancy is necessary.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization criteria categorize individuals aged 65 years and older as ‘elderly’ [1]. According to the Korea Statistical Office, elderly people will account for 28.7% of the Korean population by 2035 [2]. Moreover, the life expectancy of Korean women born in 2030 is projected to be 86.7 years, which is the longest in the world [3]. As the average life expectancy increases, the proportion of elderly patients with breast cancer is also projected to rise. Despite the expected increase in elderly breast cancer patients, there is insufficient evidence regarding the most suitable treatment for these women.

It is difficult to determine suitable therapeutic plans in these patients because aging is a complex and heterogeneous process in which chronological age does not always reflect the physiological state. A variety of factors should be considered when treating geriatric patients, including comorbidities, life expectancy, cognitive ability, performance status, concurrent medication, and socioeconomic support [4,5]. Elderly breast cancer patients tend to be undertreated for the reasons mentioned above and the survival rate of elderly patients who are undertreated is lower than that of those who receive adjuvant systemic therapy [6-9]. Moreover, the prognostic factors associated with older patients with breast cancer may include not only age but also comorbidities. Elderly breast cancer patients with multiple comorbidities have high rates of mortality and complications associated with adjuvant therapy [10-14].

Therefore, it is necessary to understand how elderly patients with breast cancer are treated and to improve the quality of current care. This study investigated the patterns of treatment and prognostic factors associated with survival in elderly patients with breast cancer.

METHODS

Patients and data collection

We retrospectively reviewed the data of 560 patients over 65 years of age who underwent surgery for breast cancer at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between 2003 and 2014. Patients with stage IV cancer (n=17), coexisting cancers of other organs (n=53), ductal carcinoma in situ (n=97), and solid neuroendocrine cancer or malignant adenomyoepithelioma (n=16) were excluded. A total of 362 patients were included in the analysis. Figure 1 shows a diagram of the patient selection process. The Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital approved this study (IRB No. B-1708/412-135). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective study design.

Data on the type of surgery in the breast and axilla; comorbidities; histologic type; histologic grade (HG); stage; estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression; adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapy); and disease status at the last follow-up visit were collected from electronic medical records (EMRs). Data on survival status were collected in conjunction with the Ministry of the Interior and Safety. Our study classified comorbidities into four categories (0, 1, 2, and ≥3) using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), which is composed of 19 disease groups assigning scores of 1, 2, 3, and 6 to each of a patient’s comorbid conditions [15]. Histologic type was divided into favorable (tubular carcinoma and mucinous carcinoma) and usual (invasive ductal carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma, metaplastic carcinoma, and mixed ductal & lobular carcinoma) types. The staging system was based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition [16]. Breast cancer subtypes were classified as luminal type A, luminal type B, HER2-enriched, and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) on based on ER, PR, HER2, and Ki-67 expression, as suggested by the 2013 St. Gallen Consensus [17]. Samples were defined as hormone receptor-positive when at least 1% of cells were positive by immunohistochemistry. The Ki-67 index was divided into high (≥14%) and low (<14%) expression. The adjuvant chemotherapy regimens administered included doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC); AC plus docetaxel; epirubicin and cyclophosphamide; cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF); fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide; and cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and fluorouracil.

Statistical analysis

The patients were divided into early-aged (65–74 years, n=277) and late-aged (≥75 years, n=85) groups. The differences between the early-aged and late-aged groups were analyzed using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Overall survival (OS) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) were estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank tests were used to compare survival differences according to patient characteristics. Distant metastasis included recurrence in the contralateral breast, cervical lymph nodes (level I–V), contralateral lymph nodes (axillary, internal mammary, supraclavicular, and infraclavicular lymph nodes), bone, and visceral organs (lung, liver, and other organs) [18]. Follow-up was completed on July 31, 2017. OS was defined as the time interval from the date of breast cancer surgery to the date of death from any cause or the last follow-up date. DMFS was defined as the time interval from the date of breast cancer surgery to the date of distant metastasis. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were used to evaluate prognostic factors. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

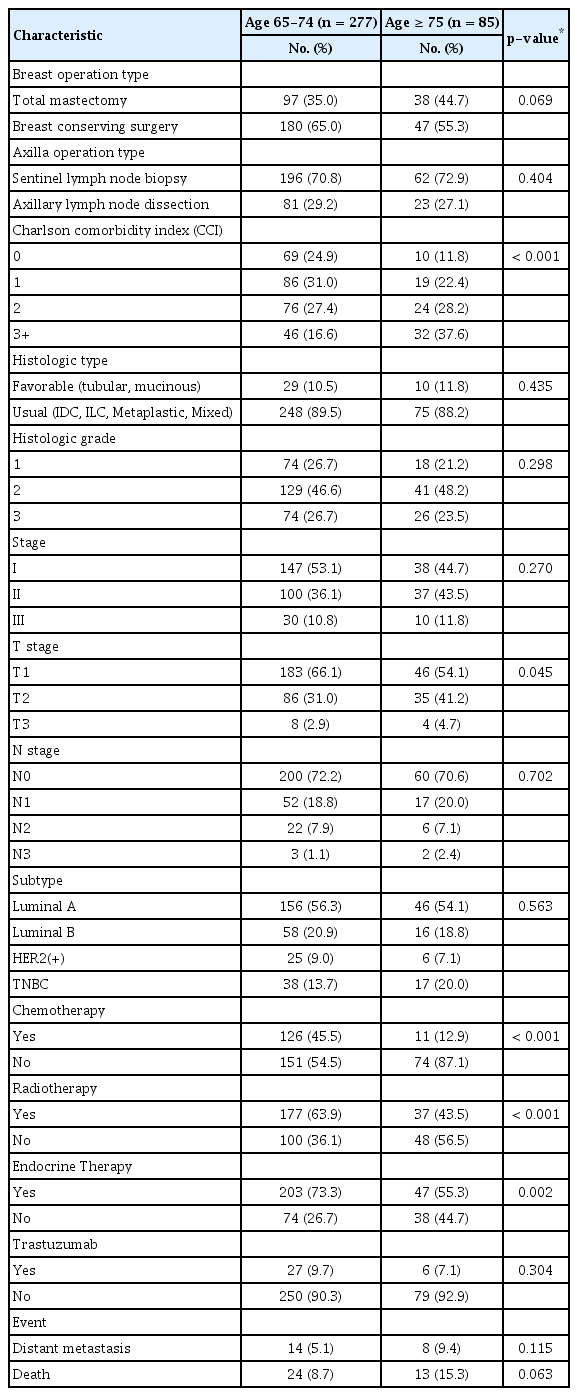

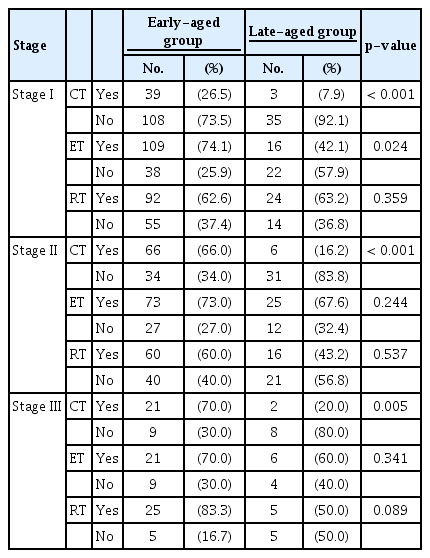

We analyzed 362 elderly patients with stage I–III breast cancer. Their mean age was 71.1 years (range 65–88 years). We compared clinicopathological characteristics between the early-aged and late-aged groups (Table 1). The surgery types for the breast and axilla, histologic type, HG, stage, subtype, and target therapy (trastuzumab) were similar between groups. The proportion of patients with CCI≥3 was higher in the late-aged group than that in the early-aged group (37.6% vs. 16.6%, p<0.001). Although no difference in stage distribution was observed between the two groups, significantly higher proportions of patients in the early-aged group received chemotherapy (45.5% vs. 12.9%, p<0.001) and radiotherapy (63.9% vs. 43.5%, p<0.001). Even when analyzed by stage, the proportion of patients who underwent chemotherapy was significantly higher in the early-aged group than that in the late-aged group for each stage (Table 2).

Clinical outcomes

The median follow-up period was 76.7 months (range 30–165 months). Distant metastasis was detected in 14 (5.1%) and eight (9.4%) patients in the early-aged and late-aged groups, respectively. The sites of distant metastasis were the lung (n=7), liver (n=5), bone (n=4), and contralateral breast (n=3) and three patients had multiple metastases. Twenty-four and 13 patients in the early-aged and late-aged groups died, respectively. EMR review revealed two patients with chemotherapy-related deaths (pancytopenia and cardiac toxicity, respectively), eight patients with deaths due to breast cancer progression, and 11 patients with deaths from other causes (two from brain infarction; two from gastric ulcer bleeding; and one each from gastric angiodysplasia, Parkinson disease, biliary sepsis, primary biliary cirrhosis, superior vena cava syndrome, lymphoma, and angina). We could not confirm the cause of death in 16 patients (43%) due to loss from follow-up. In the entire cohort, the 5-year DMFS and OS were 96.2% and 93.5%, respectively. Survival by age, HG, stage, CCI, and subtype are shown in Figure 2. The OS was lower in patients with a higher HG (96.3% for grade 1 vs. 87.1% for grade 3, p=0.004), higher stage (96.0% for stage I vs. 80.9% for stage III, p<0.001), and higher CCI score (96.1% for CCI 0 vs. 84.1% for CCI 3, p<0.001). Similar results were observed for DMFS. Regarding subtype, OS and DMFS were lowest in patients with TNBC. Additionally, the late-aged group had poorer OS than that in the early-aged group (91.8% vs. 94.0%, p=0.046). Figures 3 and 4 show DMFS and OS, respectively, by administration of chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and radiotherapy in the early-aged and late-aged groups. In the early-aged group, chemotherapy was associated with worse DMFS while endocrine therapy was related to better DMFS and OS. Patients in the late-aged group who received chemotherapy had worse DMFS and OS than those who did not (DMFS, 63.6% vs. 97.7%, p<0.001; OS, 79.5% vs. 93.6%, p=0.012).

Distant metastasis-free survival and overall survival by age (A). Histologic grade (B), stage (C), Charlson comorbidity index (D). Subtype (E).

Distant metastasis-free survival according to adjuvant treatments between the early-aged and late-aged groups.

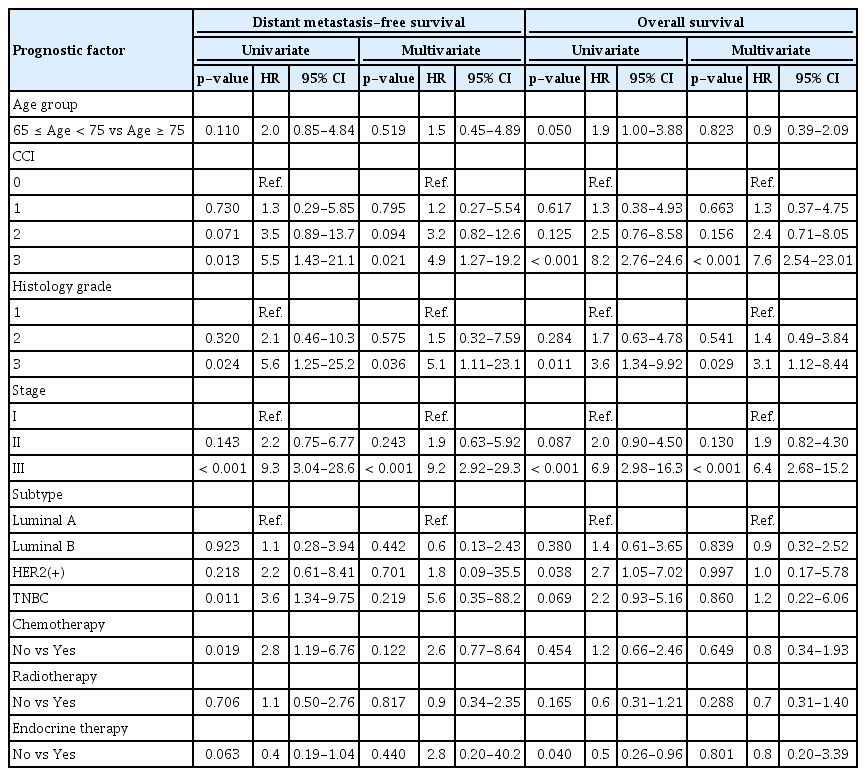

Factors associated with survival

The results of univariable and multivariable analyses to determine factors related to DMFS and OS are shown in Table 3. Multivariable analysis showed multiple comorbidities, high HG, and advanced stage to be independent prognostic factors for poor DMFS and OS. However, subtype and administration of adjuvant treatments, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormonal therapy, were not significantly associated with improved DMFS and OS.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the treatment patterns and clinical outcomes of elderly patients with breast cancer. Patients in the late-aged group (≥75 years) had more comorbidities and were less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy after breast cancer surgery. In multivariable analyses, higher comorbidities, HG, and stage were poor prognostic factors. The administration of adjuvant treatments did not affect prognosis in our elderly patients with breast cancer.

Several studies have reported that elderly breast cancer patients are less likely to receive adjuvant systemic therapy [19,20]. Hurria et al. [19] reported that only 5.2% of patients older than 75 years received adjuvant chemotherapy and that the proportion of patients receiving tamoxifen decreased with age (89% of patients 75–79 years and 79% of patients ≥80 years). Yamada et al. [20] showed that patients were less likely to receive adjuvant systemic therapy as age increased (93.6% of patients ≤65 years, 90.5% of patients 65–74 years, and 78.0% of patients ≥75 years). Similarly, patients in the late-aged group in our study were also less likely to receive adjuvant systemic treatment even though similar oncological features were observed between the early-aged and late-aged groups. However, the International Society of Geriatric Oncology recommends that patients over 70 years of age receive the same treatment as younger patients in terms of surgery and adjuvant systemic therapy. Moreover, adjuvant chemotherapy should not simply be determined by age but should rather consider the patient’s life expectancy and the potential benefit of treatment [21]. Bonadonna et al. [22] evaluated differences in recurrence and mortality among 386 patients over 75 years of age who underwent radical mastectomy (n=179) only or who also underwent 12 months of CMF after surgery (n=207). They reported that adjuvant chemotherapy reduced the relative risk of relapse by 34% and the risk of mortality by 26% over 20 years. However, they did not consider the impact of comorbidities on prognosis. Some studies that have considered the effects of accompanying diseases have shown different clinical outcomes in elderly patients [23,24]. Braithwaite et al. [23] evaluated mortality according to CCI score (0, 1, and ≥2) in 2272 patients, reporting that a higher CCI score was independently associated with an increased overall risk of death (hazard ratio [HR], 1.32; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.13–1.54), death from non-breast cancer causes (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.19–2.02), and breast cancer-specific death (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.03–2.09). Muss et al. [24] examined the toxic effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in three age groups (≤ 50 years [n=3,506], 51–64 years [n=2,439], and 65 years [n=542]), reporting higher chemotherapy-related mortality in elderly patients that increased linearly with age (0.2% [≤50 years], 0.7% [51–64 years], and 1.5% [≥65 years], p<0.001). Multivariable analyses showed that smaller tumor size, fewer positive lymph nodes, less chemotherapy, and fewer comorbidities were significantly related to longer disease-free survival and OS (p<0.001). Our study also showed a significant association between having more comorbidities (higher CCI score) and poor DMFS and OS in multivariable analysis. Moreover, the administration of adjuvant treatments, including chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and radiotherapy, was not associated with improved DMFS and OS. These results may suggest that systemic treatment in elderly patients has the potential to worsen, rather than improve, health status and underlying diseases such as heart disease. Doyle et al. [25] reported cardiac toxicity associated with chemotherapy in elderly patients (>65 years). The HRs of cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, and heart disease in patients treated with chemotherapy compared to those in patients who received no chemotherapy were 2.48 (95% CI, 2.10–2.93), 1.38 (95% CI, 1.25–1.52), and 1.35 (95% CI, 1.26–1.44), respectively. Garg et al. [26] assessed the relationship between CCI and chemotherapy toxicity in 65 elderly (≥70 years) patients and found increasing age, lower functional status, and high CCI to be associated with an increased discontinuation rate, dose reduction, and grade 3–4 toxicity.

Elderly patients with breast cancer are more likely to have ER-positive tumors that respond well to hormonal agents and are associated with a slightly better overall prognosis and reduced recurrence rate [27]. In the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group analysis of patients with ER-positive breast cancer, 5 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy with tamoxifen reduced the annual recurrence rate at 15 years by 34% in women aged 50–59, 45% in women aged 60–69, and 51% in women older than 70 years. Among these patient groups, the annual death rate was also reduced by 24%, 35%, and 37%, respectively [28]. In another study, the effects of adjuvant endocrine therapy differed based on comorbidity. Land et al. [29] evaluated the breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) by CCI score in elderly patients who received endocrine therapy, reporting lower BCSS in patients with higher CCI scores (1, 2, and ≥3) than that in patients without comorbidity (HR 1.23 [95% CI, 1.09–1.39] for CCI 1, HR 1.28 [95% CI, 1.05–1.55] for CCI 2, and HR 1.60 [95% CI, 1.23–2.07] for CCI 3). We also observed an increased risk of systemic relapse and overall mortality with increasing CCI score, but they were not affected by endocrine therapy.

Molecular subtype is a well-known prognostic factor of breast cancer, with the TNBC and luminal A subtypes showing the worst and the best prognoses, respectively. However, some studies have reported no difference in prognosis according to subtype in elderly patients. de Kruijf et al. [30] reported an association between molecular subtypes and prognosis in young patients (<65 years; n=361) based on the relapse-free period (RFP) (p=0.01) and relative survival (RS) (p<0.001). However, they observed no significant prognostic effect of subtype in elderly patients (≥65 years; n=189; RFP p=0.5; RS p=0.1). Similarly, multivariable analysis in the present study also revealed no significant difference in prognosis based on subtype.

This study has several limitations. First, our study was a retrospective study performed in a single institution. A critical drawback of the retrospective design was that the therapeutic decision-making process in elderly patients was not clear. It was difficult to prove a causal relationship between adjuvant treatment and survival improvement. In elderly patients, there is the potential for selection bias because adjuvant therapies may be limited depending on accompanying disease, age, or patient preferences. Moreover, the small number of samples made it difficult to perform meaningful multivariable analysis of heterogeneous factors associated with treatment. Second, we could not analyze BCSS. The cause of death for patients who continued to visit our hospital was confirmed by EMR. However, due to follow-up loss, the cause of death could not be identified in 43% of all deaths. We, therefore, evaluated the overall mortality and related prognostic factors. Third, CCI is generally a tool used to assess comorbidity but does not reflect disease severity or patient performance status. A more comprehensive assessment of comorbidity in elderly patients, such as the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, could assist in determining the treatment process.

Recent demographic changes suggest that the number of older patients with breast cancer will continue to increase; thus, clinicians need to be prepared to treat this patient population. Although it is recommended that elderly breast cancer patients be as actively treated as young patients, the results of our study showed that adjuvant treatments were not associated with prognosis; furthermore, higher HG, stage, and CCI score were independently associated with poor prognosis in multivariate analysis. Therefore, treatment planning for elderly patients must consider various factors including not only important clinical features such as stage and subtype but also comorbidities, performance status, and life expectancy. Since, as a retrospective study in a single institution, this study has several limitations, it is difficult to conclude the effect of adjuvant therapy in elderly patients. Guidelines must be established for the treatment of breast cancer in elderly patients and the study of its therapeutic effects should be expanded.

Notes

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Division of Statistics of the Medical Research Collaborating Center at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital for performing the statistical analyses.