INTRODUCTION

According to the third national health and nutrition survey of Korea, which was reported in 2001 and included a total of 6,569 Korean adults [1,2], the nation’s overall prevalence of obesity (defined as body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25 kg/m2) was 30.6% (32.4% and 29.4% in men and women, respectively). Previously, Song et al. [3] reported a dramatic increase in obesity rates (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) in South Korea over a period of 11 years. Concurrently, the incidence and risk of obesity-related disease increased.

In general, obesity is regarded as a risk and poor prognostic factor in some types of breast cancer. Obese patients tend to have larger tumors and more positive nodes [4]. Several reports have suggested that obesity leads to poor prognosis by increasing circulating plasma levels of estrogen, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor that promote tumor growth [5,6]. Recent meta-analyses have examined the relationship between BMI and survival in a large number of patients [7,8]. Chan [8] analyzed data from 213,075 patients across 82 studies, summarizing relative risk of overall and breast cancer-specific mortality in obese vs. normal-weight patients at baseline as 1.41 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.29-1.53) and 1.35 (95% CI, 1.24-1.47), respectively.

Compared to Western populations, in Korea, the prevalence of breast cancer in patients younger than 50 years is higher; these women tend to have relatively lower BMI than women aged 50 years and above [9,10]. These population differences might be indicative of the role of obesity in breast cancer. However, the impact of obesity might be mediated by patient age in addition to ethnicity. For example, Asian populations tend to have a proportionally higher total body and abdomen fat percentage than Caucasians; as a result, these populations tend to develop obesity-related complications at relatively lower BMI [11]. The Korean Health Insurance Service (NHIS) developed the Korean obesity index standard reference (KOISR) in 2016 as a tool for individual obesity assessment in the Korean context [12]. Actually, the KOISR is a representative tool; for example, in Korea, women in their twenties have relatively normal BMI, women above the 75th percentile were considered as having normal BMI, but women in their mid-forties above the 75th percentile had BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 [13].

However, previous studies [14,15] in Korea have used as reference different definitions of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) rather than the WHO’s criteria for Asian populations. As a result, the effects of obesity on survival may have been overestimated or underestimated. In this study, we investigated the relationship between BMI and clinical characteristics or overall survival (OS), using KOISR in a community-dwelling population.

METHODS

Study population

A single-center retrospective observational study was performed (Haeundae-paik Hospital, Busan, Korea) between January 2014 and July 2018. A total of 429 patients were diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer during this period. Male and non-Korean patients were excluded from this study, as were patients with other tumors (sarcoma, phyllodes tumor, and lymphoma). Data from a total of 418 patients were included in the final analysis; patients were categorized into three weight groups based on their BMI, according to the modified WHO obesity criteria for Asian populations (low weight: BMI < 18 kg/m2, normal weight: BMI 18 ≤ - < 25 kg/m2, obesity: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) [16]. BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. BMI was measured at the time of diagnosis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Inje University Haeundae-paik Hospital (IRB No. 2020-02-034).

The Korean obesity index standard reference

The NHIS has worked with the National Institute of Technology and the Korean Institute of Standards and Sciences to develop the KOISR, which reflects unique characteristics of Koreans; it was registered as a national reference standard on December 16, 2016. NHIS used data from 16.4 million health check records (2013, 2014), acquired during nation-wide health checks. In particular, the existing health screening data was applied to the concept of uncertainty reflecting the error range; the uncertainty and the error range of the equipment due to repetitive measurement was not covered by the more sophisticated data. The new reference was stratified by BMI, sex, age, and Korean province, and released to the public [12]. We converted all BMI data to the KOISR, and defined “high” KOISR as values within the 75th percentile or above, compared to age- and gender-matched controls sampled from the same community (Supplementary Table 1, 2).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were summarized as absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous and categorical variables were compared among BMI groups using one-way analysis of variance and the χ2 test, respectively. Survival outcomes were analyzed in terms of overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). OS was defined as the time from the first diagnosis of primary breast cancer to death from any cause and DFS was defined as time from diagnosis of breast cancer to death due to breast cancer or following a breast cancer-related event. Survival rate of patients lost to follow-up was calculated using the date of last follow-up. Survival curves for all three BMI groups were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to evaluate statistical significance of between-group differences in survival. All reported p-values were two-sided, with the level of significance established at p<0.050. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, USA).

RESULTS

Patients’ clinical characteristics and obesity

The distribution of BMI at diagnosis included 266 (63.6%), 143 (34.2%), and 9 patients (2.2%) with normal BMI, obesity, and low BMI, respectively. Concurrently, 52.6% (220/418) of patients had high KOISR scores, suggesting breast cancer patients in the studied community had higher BMI than women in the general population. BMI correlated with age; 19.4% (35/180) of patients with obesity were younger than 50 years and 45.4% (108/238) of patients with obesity were aged 50 years and above (p<0.001) (Table 1). There was no correlation between BMI at diagnosis and disease stage (p=0.090) (Table 1); however, there was a correlation between KOISR percentile and disease stage (p=0.030) (Table 2). In addition, postmenopausal women had a positive correlation with obesity (Table 1, 2). Specifically, advanced stage disease (stage III/IV) was more likely in women with high KOISR scores (Figure 1). Correlations between other clinical factors and BMI or the KOISR are shown in Table 1 and 2.

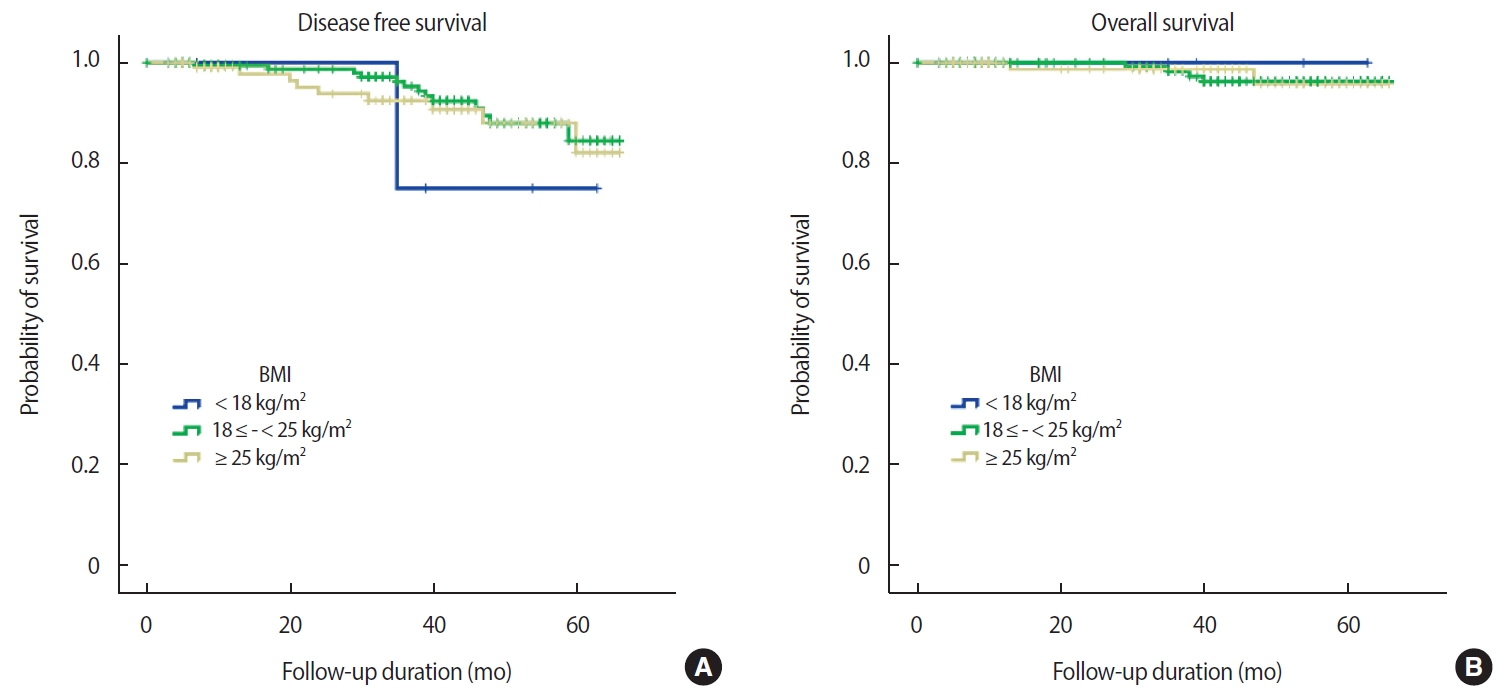

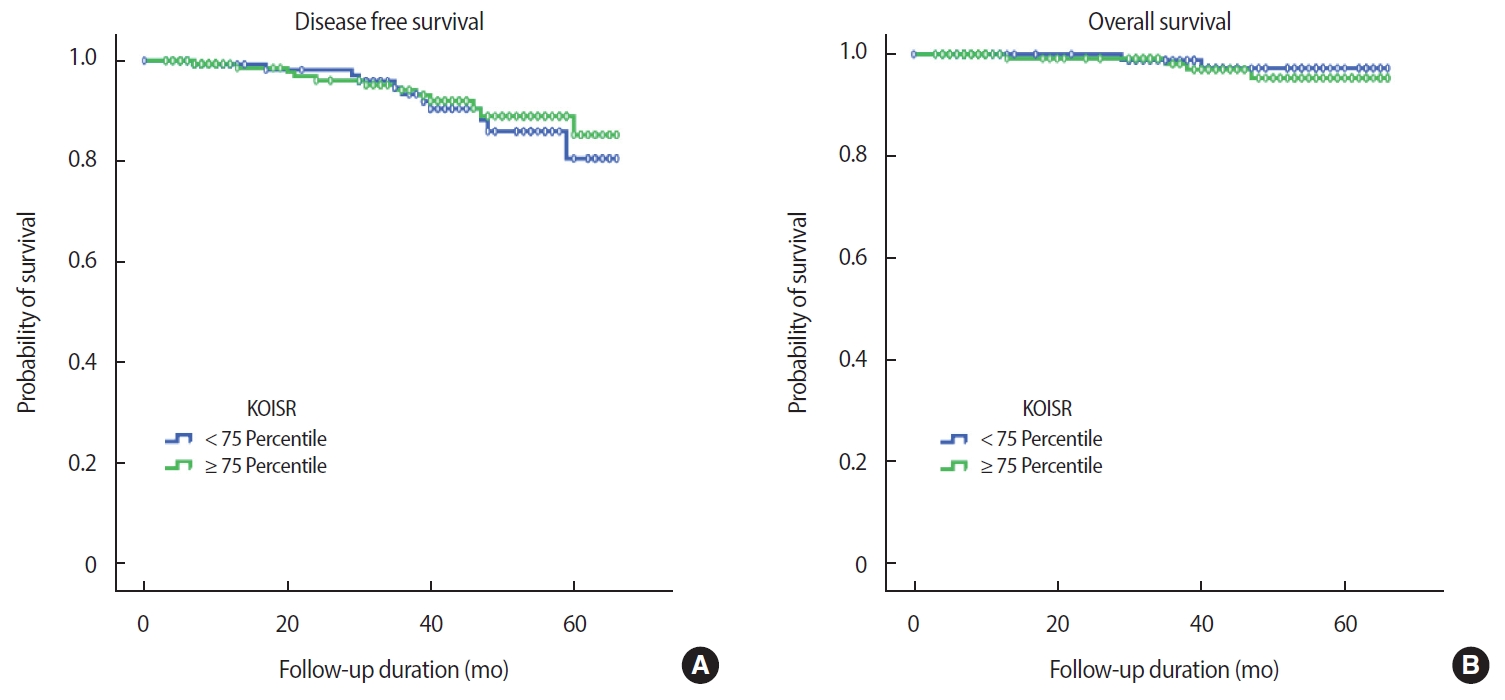

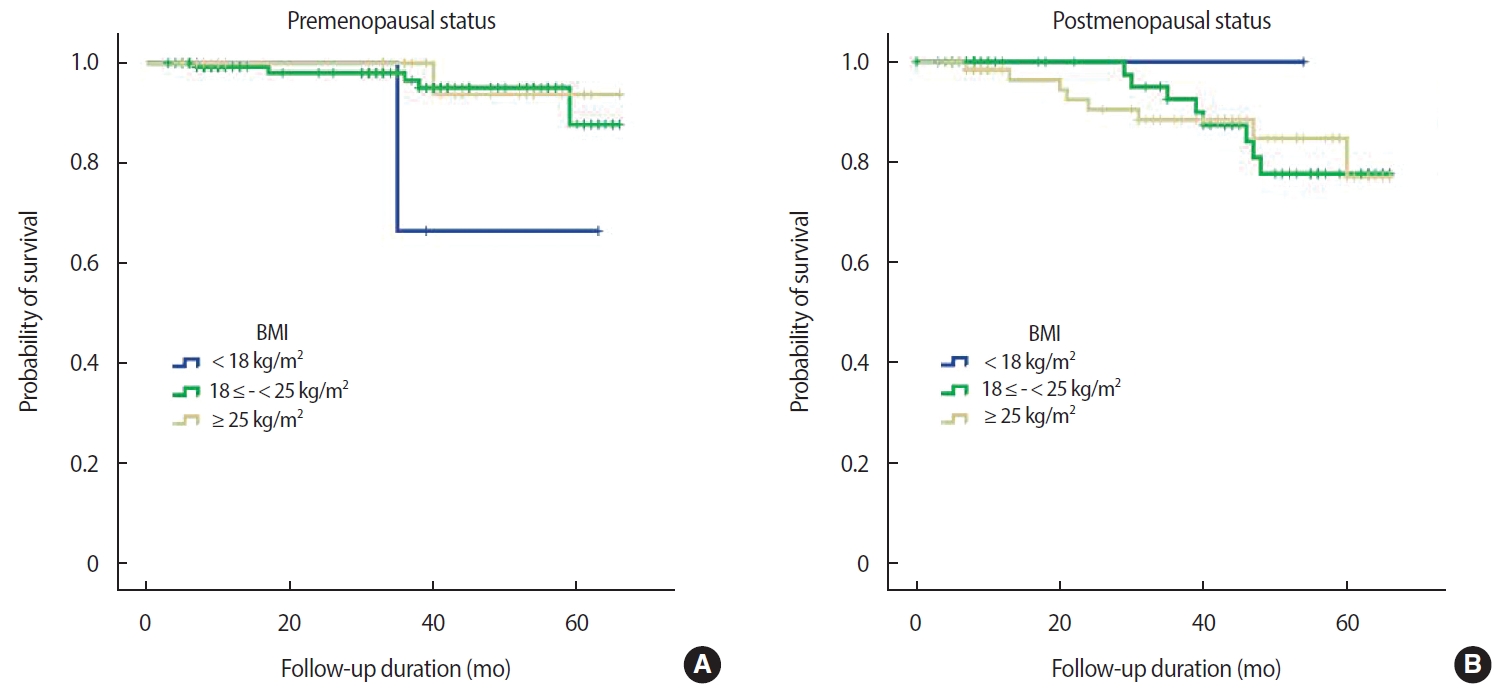

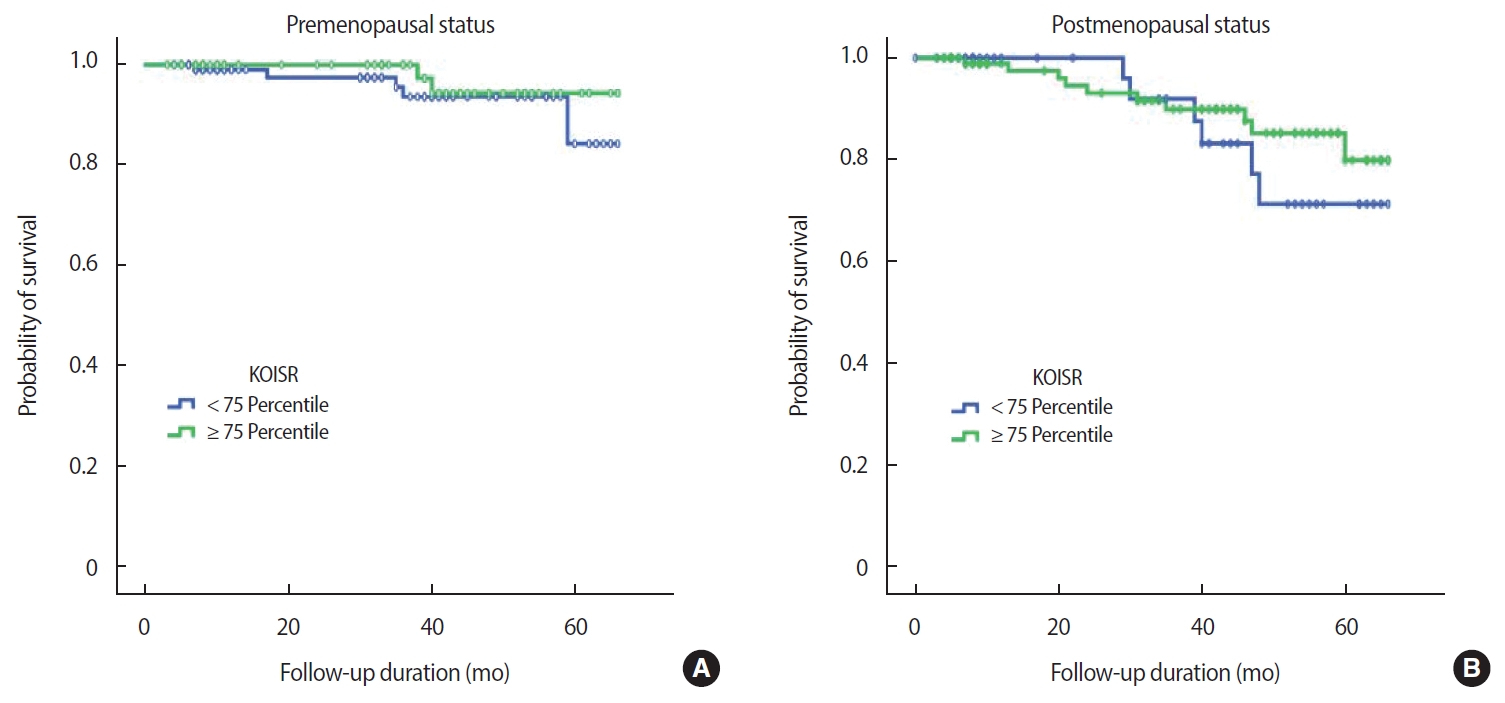

Clinical outcomes and obesity defined by BMI or the KOISR

The mean duration of follow up was 33.3 months, during which 24 events occurred (17 recurrences, 6 deaths, 1 alive with disease). After excluding patients with in situ cancer (113 patients), data from 305 patients with invasive breast cancer were analyzed (24 events). There was no relationship between either OS or DFS and BMI at diagnosis (OS, p=0.980; DFS, p=0.900) (Figure 2). This finding was consistent with that achieved using the KOISR (OS, p = 0.340; DFS, p = 0.940) (Figure 3). When analyzed by menopausal status, DFS did not show any correlation with either status of BMI (p=0.630) (Figure 4) or KOISR (p=0.240) (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

This is the first Korean community-based study of the relationship between obesity and survival among breast cancer patients, using data from medical records. Previous retrospective studies on Korean breast cancer patients were large, multi-center, nationwide studies that included relatively younger breast cancer patients [14,15]. Both Busan and Kyung-Nam province have aging populations; the median age of breast cancer patients therein was higher than the median age of breast cancer patients across Korea [17]. Since 2010, the chronological peak incidence has moved to later in life, with the present median age of onset estimated at 50 years [10]. Although the association between high BMI and breast cancer risk is well established, it is based on evidence from studies conducted in Western countries. In East Asia, Chow et al. [18] found that BMI at diagnosis was positively correlated with the risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal, but not premenopausal, women. Kang et al. [19] showed that an increase in BMI positively correlated with breast cancer incidence through a single-center’s screening data (odds ratio n =2.09, p=0.012) in Korea. In Japan, a nationwide prospective sister cohort study suggested that postmenopausal women who are metabolically unhealthy (defined based on characteristics such as elevated blood pressure, antidiabetic drug use, or cholesterol-lowering medication use) may be at increased risk of breast cancer despite normal BMI. Additionally, an inverse association between premenopausal breast cancer risk and the metabolically healthy overweight/obese phenotype (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.52-0.97) has been reported [20].

The presence of a positive association between advanced disease stage at diagnosis and obesity has been corroborated by several studies [21,22]. Deglise et al. [22] reported on a population-based study, showing that obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) affects presentation and diagnostic assessment of women with breast cancer. Obese women were nearly twice as likely as their normal-/under-weight counterparts to present with advanced stage (stage III/IV) disease at diagnosis. Cui et al. [23] hypothesized that increased breast size in obese women may delay discovery of a breast tumor. As a result, the relationship between obesity and breast cancer stage at diagnosis was stronger among women younger than 50 years than among women aged 50 years or older. Also, this finding may be of considerable concern, given the increasing prevalence of obesity in the United States and the prognosis associated with late-stage tumors, but in Korea, where additional ultrasonography has been a popular screening method, this hypothesis needs to be studied for women with small- or medium-sized breasts. High BMI increased the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women in Western countries and in Westernized Asia. It is plausible that various biological factors related to obesity might stimulate tumor progression. For example, a high concentration of bioavailable estrogen due to aromatization of circulating androgens to estrogen in adipose tissues may have a mitogenic effect on breast cancer cells. However, the hypothesis that high BMI is associated with lower levels of aromatase inhibitors due to increased amount of adipose tissue and aromatase activity was not supported in multivariate analysis [24].

Previous studies on the association between BMI and breast cancer prognosis in Asian women showed that high BMI [15,25] (≥ 25 kg/m2) had an adverse effect on OS but not on DFS. Furthermore, stratified by age, BMI was significantly and negatively associated with OS in patients aged 50 years and above; however, this effect was not detected in younger Chinese women. Duration of follow-up could account for this discrepancy. The TEAM (tamoxifen exemestane adjuvant multinational) trial showed an adverse association between short-term (2.75 years) cancer prognosis and obesity in patients on adjuvant tamoxifen; however, this association did not hold over a long term (5.1 years) [26].

Several previous studies have shown a relationship between obesity and either OS or DFS. Kamineni et al. [27] reported that, compared to normal-weight women, obese women are at increased risk of disease recurrence and disease-specific mortality within 10 years of diagnosis with rates estimated at 12.2% and 6.9%, respectively. Although there is no association between BMI and all-cause mortality, obese women have been shown to have significantly faster-growing tumors. This study involved a cohort of 3,385 women enrolled in the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project protocol B-14, which showed no association between obesity and increased risk of recurrence in lymph node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer; however, the same study revealed an association between obesity and increased risk of contralateral breast cancer and all-cause premature mortality [28].

Considering breast cancer stage, moderate to severe obesity is associated with poor prognosis in invasive breast cancer; this association was also detected in women with stage I disease, and was independent of age and treatment [29]. Gennari et al. [30] showed that higher BMI did not influence prognosis in high-risk early breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy. These authors suggest that in an aggressive biological subtype of breast cancer, the impact of host factors on patient prognosis could be minor.

In conclusion, women with high BMI (KOISR ≥ 75th percentile) has a positive association with risk of breast cancer in all ages, as well as a positive correlation with advanced breast cancers. Although the clinical usefulness of the KOISR needs to be studied further, it may be a more representative reference to explain the status of individual obesity in patients with breast cancer. Despite a short follow-up period, obesity did not have an adverse effect on OS; however, whether this effect differed between disease stage (early vs. advanced) remains unclear. Additionally, relevant evidence should be incorporated into comorbidity assessment.